MCMC - The MH Algo

MCMC - The Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

Sampling from an unknown distribution can be relatively difficult. Distributions allow for the calculations of many stationary parameters associated with the distribution. For a given probability distribution \(\rho(x)\) for example, where \(x\) is defined over \(x \in [0,1]\), Several important quantities may be calculated with this distribution. For example,

,

In a lot of circumstances, the integrals are practically impossible to calculate in closed form. It might be possible to do numerical integrations over small dimensional spaces or those where the distribution in integrable, but due to the curse of dimensionality, these methods may not be entirely possible.

An entirely different approach is to sample points with the given distribution. Then, the integrals above reduce to summations. That is, given a sample \(X = [x_1, \ldots, x_N]\) for large \(N\), where \(X\) is drawn from the same distribution as \(\rho(x)\), the expectations can simply be calculated as:

(Note that the \(1/N\) only holds for large \(N\) in general, but let us not worry about such details).

The question of course is, how do we do this sampling in an efficient way?

First, lets look an an inefficient way. In this method, we generate two sets of numbers: \([ (x_1, y_1), (x_2, y_2), \ldots ]\). Now given the distribution \(\rho(x)\), we filter out the values of \(x_i\) where \(\rho(x_i) < y_i\). In python, it will look something like: [x for x,y in vals if rho(x)<y].

How many such numbers do we need to generate? Let us take the trivial example of the Beta distribution. We need to cover \(0 \leq x \leq 1\), and \(0 \leq y \leq \textrm{mode}( \textrm{Beta}(x) ) \). Depending upon the skew of the distribution, we are generating \( \textrm{mode}( \textrm{Beta}(\alpha, \beta)) \) times the points that we really need. The greater the skew in the distribution, the higher this value. What is more, the higher the dimensionality of the space that we are trying to traverse, the worse this problem gets.

There is a class of algorithms that belong to the MCMC method that approximates the solution to the problem fairly well. Markov chains (MCs) are state-space problems whose progression to the next state depends solely upon the current state. Given states \( { X_1, X_2 , \ldots, X_N } \), for the transition \( X_i \rightarrow X_j \),

Monte Carlo (the other MC) methods are simply methods of different methods of sampling. MCMC comprises of a set of algorithms that use some very clever methods of sampling distributions. Some of the more popular ones are the the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm, Gibbs sampling, and the slice algorithm. The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm forms the basis of the more complicated Gibbs sampler, so we shall investigate it here.

The idea of this algorithm is to hover around spaces that have greater distribution probability. Given a random starting point in the input space, the algorithm steps through other states, either accepting or rejecting the next state as a legitimate state. For this to work, however, two conditions need to be met:

- The chain should be able to span the entire space.

- Detailed balance, which amounts to:

This is going to make sure that the chain wont get stuck in loops.

Now, give that we are in state \(X_i\), we need to figure out how to

- Select a random state \(X_j\) to jump to, and

- Determine if this new state \(X_j\) is worth making a jump to. And if it isn’t, remain in state \(X_i\)

1. Selecting a random state to jump to:

This is typically done by jumping to a nearby point with a normal distribution. For example, if is a state in an \((M+1)\) dimensional space given by the coordinates \(X_i = (x_{i0}, x_{i1}, \ldots, x_{iM} )\), then a jump to the next state can simply be given by:

Here, \( N(0, \sigma_k) \) represents a random point selected from a normal distribution with standard deviation \( \sigma_k \). Performance improvements often modify this criterion such that this is done more intelligently.

2. Determine is the new state is a good one to jump to:

This one is actually neat. Let us say that there is an “acceptance distribution”

Then, the probability of moving to the new state is given by:

Given the above equation, and detailed balance, we come to the following equation:

We will accept the new state if the numerator is higher than the denominator. So let us write a small function to test this out …

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import beta

def MHalgo(dist, N=100):

results = []

i = 0

xOld = np.random.uniform()

yOld = dist.pdf( xOld )

stepSize = 0.05

sampleSize = 2

while True:

i+= 1

if len(results) >= N:

return np.array(results[:N])

xNew = xOld

while True:

xNew = xOld + np.random.normal(0, stepSize)

if (xNew <=1) and (xNew >= 0): break

yNew = dist.pdf(xNew)

if (yNew >= yOld) or (yNew/yOld > np.random.rand()):

xOld, yOld = xNew, yNew

if i%sampleSize == 0:

results.append(xNew)

return np.array(results)

def main():

a, b = 2, 4

N = 10000

xInit, xEnd = beta.ppf([0.001, 0.999], a, b)

x = np.linspace(xInit, xEnd, N)

bta = beta(a, b)

points = bta.rvs(size=N)

points1 = MHalgo(bta, N=N)

plt.plot(x, bta.pdf(x), label='$\\beta({},{})$'.format(a, b) )

plt.xlabel('$x$')

plt.ylabel('$\\beta$')

yHist, xHist, _ = plt.hist(points,

bins=60, normed=True, alpha=0.5,

label='original')

yHist, xHist, _ = plt.hist(points1,

bins=60, normed=True, alpha=0.5,

label='MH algo')

plt.legend(loc='upper right')

plt.savefig('MH-result.png')

print('Mean of points = ', points.mean())

print('Mean of MH algo = ', points1.mean())

print('a / (a + b) = ', a/(a+b))

print('Variance of points = ', (points**2).mean())

print('Variance of MH algo = ', (points1**2).mean())

print('a*(a+1) / ((a+b+1)*(a + b)) = ', a*(a+1) / ((a+b+1)*(a + b)))

plt.show()

return xHist, yHist

if __name__ == '__main__':

xHist, yHist = main()

plt.close('all')

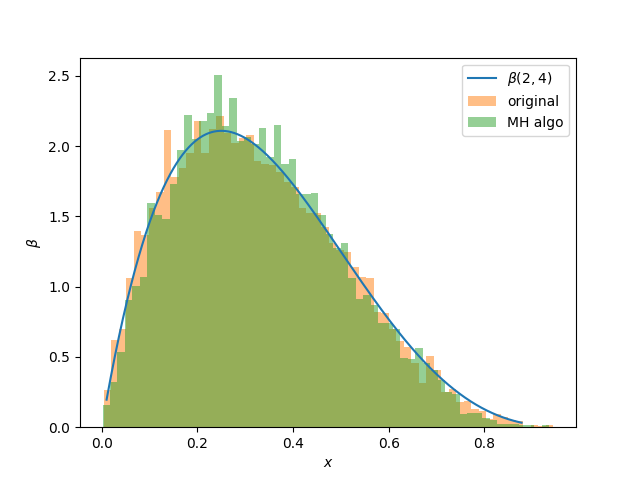

How does it fare?The program plots the following distribution, one from samplings obtained from the scipy.stats package, and another from the algorithm just described.

As can be seen the results are very promising:

Mean and variances of the distribution are also estimated from both distributions, and compared with calculated values. Both mean and variances compare favorably with the expected result as seen below.

Mean of points = 0.328379757064

Mean of MH algo = 0.330756246665

a / (a + b) = 0.3333333333333333

Variance of points = 0.144005175893

Variance of MH algo = 0.143690856643

a*(a+1) / ((a+b+1)*(a + b)) = 0.14285714285714285