When Order Emancipates

When Order Emancipates

Some people find structure stifling. However there are legitimate places where order becomes outright liberating. These cases typically revolve around routine tasks.

Let us take for example the task of logging information on long-running processes. This is a de-facto standard of concurrent programming practice. Let us elucidate this with an example.

Note that what follows is the simplest rendition of an example that retains features necessary for describing the idea of fixing structure. A real Python project typically has many more items, all of which have been stripped from this example, to keep it simple.

1. The natural order of things

We want to initiate a project with some form of logging facility. We would probably do something like this:

import logging, os

from datetime import datetime as dt

from time import time

def someFunction():

logger = logging.getLogger('someBase.someFunction')

logger.info('Started function')

t0 = time()

print("Hello Word!!!")

t = time() - t0

logger.info('Finished function. Execution time: {0:.2f} seconds'.format(t))

return

def main():

logger = logging.getLogger('somebase')

formatter = logging.Formatter('%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

fH = logging.FileHandler(os.path.join(

'path/to/logFolder',

dt.now().strftime('%Y-%m-%d_%H-%M-%S') +'.log'))

fH.setFormatter(formatter)

logger.addHandler(fH)

logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)

logger.info('Program started')

someFunction()

logger.info('Program finished!!')

return

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

2. So what is your problem with this you might ask?

- I am lazy, and this is a hell-of-a-lot-of-typing to do for printing

Hello World!. Surely, we can do better? If we have to do this in every project, then this is a bit of wasted time isn’t it? - More importantly, there must be an elegant solution. I am not such a great fan of the

COPY-PASTE.

So, how do we generalize this? First, let us look at items within this document that are specific to this project, and what can be easily factored out? The following are specific to the porject:

- line 6, 19:

'somebase': The root of the logging breadcrumb - line 22:

'path/to/logFolder'

Note that the following items are not specific to the project. They are specific to the program/function/class/library, or whatsoever you would not have in every porject.

- line 6: the rest of the breadcrumb

'.someFunction'

2.1. Creating a structure to be used all the time

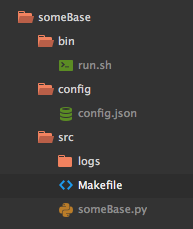

For this specific task, let us create a very simple project structure as shown below:

“Woah! Woah! Woah! Hold on there a minute! Now we have to create four folders and 4 different files to print Hellow World!?,” you say. Aren’t we moving in the opposite direction to simplification-land? As we will see later, we can automate this process. So all the files/folders we want will be automatically generated. But we are getting ahead of ourselves. How do these additional files and folders help? The answer lies in the structure. If we always use this same structure, then

- The

path/to/logFolderis always fixed tosrc/logs, and somebasecan now be saved in the fileconfig/config.jsonfile.

2.2. Saving project-specific configuration

The file config\config.json can contain any number of configuration parameters. For now, let us just save the value of the root of the logging for breadcrumbs. It will look like:

{ "logBase":"somebase"}

2.3. Replace project-specific information within the file

Now, let’s consider the rewritten file src\someBase.py

import logging, os, json

from datetime import datetime as dt

from time import time

def someFunction():

config = json.load(open('../config/config.json'))

logger = logging.getLogger('{}.someFunction'.format(config['logBase']))

logger.info('Started function')

t0 = time()

try:

print("Hello Word!!!")

except Exception as e:

logging.error('Unable to print Hello World: {}'.format(str(e)))

t = time() - t0

logger.info('Finished function. Execution time: {0:.2f} seconds'.format(t))

return

def main():

config = json.load(open('../config/config.json'))

logger = logging.getLogger(config['logBase'])

formatter = logging.Formatter('%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

fH = logging.FileHandler(os.path.join(

'logs',

dt.now().strftime('%Y-%m-%d_%H-%M-%S') +'.log'))

fH.setFormatter(formatter)

logger.addHandler(fH)

logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)

logger.info('Program started')

someFunction()

logger.info('Program finished!!')

return

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

As you can tell, there are two main changes.

- The location of the log file is now hardcoded (line 29) [the result of structure in our projects], and

- The base of our logging breadcrumb is saved in a config file. This can subsequently be used by any new function that we create.

2.4. A couple of helper functions

Every time we run the program, we want to view the log file generated to see whether there were any errors. For this, we create a simple bash script:

File: bin/run.sh

#!/bin/bash

python3 someBase.py

logFile=$(ls logs/*.log | sort | tail -n1)

# Turn this off if necessary

echo "The entire log file:"

cat $logFile

# Print the errors

echo "Errors:"

cat $logFile | grep 'ERROR'

exit 0 # Prevent an error call in the Makefile

And a really basic Makefile

grantPermissions:

chmod +x ../bin/*

run:

../bin/run.sh

2.5. Let do a dry run.

$ make grantPermissions

$ make run

../bin/run.sh

Hello Word!!!

The entire log file:

2017-08-06 22:48:05,351 - somebase - INFO - Program started

2017-08-06 22:48:05,351 - somebase.someFunction - INFO - Started function

2017-08-06 22:48:05,351 - somebase.someFunction - INFO - Finished function. Execution time: 0.00 seconds

2017-08-06 22:48:05,351 - somebase - INFO - Program finished!!

Errors:

Ok, so no errors. You will typically not print the entire log file. But that is a trivial change that you need to do.

3. With Structure Comes Structured Help

Ok. So this is still too much code to write. Where is the reduction in code that we were looking for?

It is time now to factor out redundant code into a couple of decorators. Lets generate a file within the logs folder called logs\logDecorator.py.

import json, logging

class simpleDecorator(object):

def __init__(self, base, folder='logs'):

self.base = base

self.folder = folder

return

def __call__(self, f):

from time import time

# Function to return

def wrappedF(*args, **kwargs):

logger = logging.getLogger(self.base)

logger.info('Starting the function [{}] ...'.format(f.__name__))

t0 = time()

result = f(logger, *args, **kwargs)

logger.info('Finished the function [{}] in {:.2e} seconds'.format(

f.__name__, time() - t0 ))

wrappedF.__name__ = f.__name__

wrappedF.__doc__ = f.__doc__

return result

return wrappedF

class baseDecorator(object):

def __init__(self, base, folder='logs'):

self.base = base

self.folder = folder

return

def __call__(self, f):

from datetime import datetime as dt

from time import time

# Function to return

def wrappedF(*args, **kwargs):

logger = logging.getLogger(self.base)

formatter = logging.Formatter('%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

fH = logging.FileHandler( \

self.folder + '/' + \

dt.now().strftime('%Y-%m-%d_%H-%M-%S') + \

'.log')

fH.setFormatter(formatter)

logger.addHandler(fH)

logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)

logger.info('Starting the main program ...')

t0 = time()

result = f(logger, *args, **kwargs)

logger.info('Finished the main program in {:.2e} seconds'.format( time() - t0 ))

return result

return wrappedF

Given these decorators, we can rewrite the programs as follows:

import logging, os, json

from time import time

from logs import logDecorator as lD

from datetime import datetime as dt

config = json.load(open('../config/config.json'))

base = config['logBase']

@lD.simpleDecorator('{}.someFunction'.format(base))

def someFunction(logger):

try:

print("Hello Word!!!")

except Exception as e:

logging.error('Unable to print Hello World: {}'.format(str(e)))

return

@lD.baseDecorator(base)

def main(logger):

someFunction()

return

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Ok, this looks more like it! Lets run it one more time:

$ make run

../bin/run.sh

Hello Word!!!

The entire log file:

2017-08-06 23:14:41,993 - somebase - INFO - Starting the main program ...

2017-08-06 23:14:41,993 - somebase.someFunction - INFO - Starting the function [someFunction] ...

2017-08-06 23:14:41,993 - somebase.someFunction - INFO - Finished the function [someFunction] in 2.41e-05 seconds

2017-08-06 23:14:41,993 - somebase - INFO - Finished the main program in 1.72e-04 seconds

Errors:

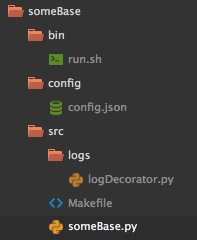

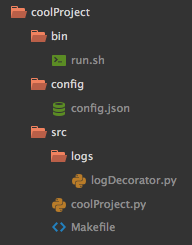

Now, the porject structure looks like the following:

4. Generating Similar Projects using cookiecutter

cookiecutter is an amazing tool that will allow you to automate the task of generating an infinite levels of directory nesting, and uses the jinja library for templating. Now, we will convert this simple example into a template that can be used over and over in other projects. How do we do this?

- Copy the entire folder contents into a convenient location.

- Generate a templating file called

cookiecutter.jsonwithin this location, and update the templates - Move your template to the

~/.cookiecutters/folder - Generate a new project with this template

4.1. Copy folder contents

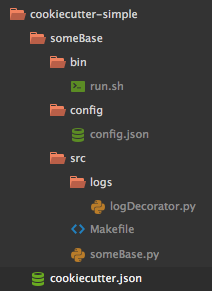

Copy the entire folder contents into a convenient location. I’ll call it cookiecutter-simple for this example. You can call it anything you like.

4.2. Generate the required templates

Create a file called cookiecutter.json at the top level. This file will contain your templating variables. We shall put in our required templating variables within this file. At this moment, the contents of the top-level structure should look like this:

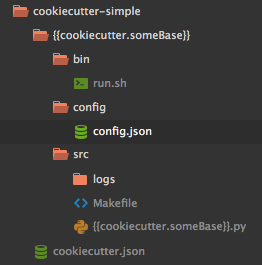

At this point, we want to change the names of the files, folders and text within files with our own templating variables. In this case, we have a single templating variable: someBase. Lets recount the places where this appears:

| No | type | Location | Changed to |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | folder name | cookiecutter-simple/someBase | cookiecutter-simple/ |

| 2 | file name | cookiecutter-simple//src/someBase.py | cookiecutter-simple//src/.py |

| 3 | file content in cookiecutter-simple//bin/run.sh, line 2 | python3 someBase.py |

python3 .py |

| 4 | file content in cookiecutter-simple//config/config.json, line 1 | { "logBase":"somebase"} |

{ "logBase":""} |

Your folder structure should now look like the following:

4.3. Generate the templating variable ‘someBase’

Now we have to tell cookiecutter what you want to change the variable someBase with. This is done in the cookiecutter.json file. Update this file with the variable that you want to specify:

{"someBase":"someBase"}

4.4 Move this entire folder to the right location.

Now that we have generated a simple cookiecutter template, we can move this entire folder to the location ~/.cookiecutters. This is where cookiecutter will look for templates.

4.5. Now generate a new project

$ cookiecutter cookiecutter-simple ↵ 1

someBase [someBase]: coolProject

And with a single line, you have created the entire project. Lets look at the new structure …

Now, we have a cool project. Let try to run it …

$ cd coolProject/src

$ ls

Makefile coolProject.py logs

$ make run

../bin/run.sh

Hello Word!!!

The entire log file:

2017-08-07 10:18:01,501 - coolProject - INFO - Starting the main program ...

2017-08-07 10:18:01,501 - coolProject.someFunction - INFO - Starting the function [someFunction] ...

2017-08-07 10:18:01,502 - coolProject.someFunction - INFO - Finished the function [someFunction] in 2.41e-05 seconds

2017-08-07 10:18:01,502 - coolProject - INFO - Finished the main program in 1.87e-04 seconds

Errors:

Well, this is what I am talking about! Write one line to create the project, and another to run it. Now since you have a template, you can create as many projects as you wish, and you will have this entire structure with you at all times.

Check out all the other cookiecutters that are already available for making readymade projects.

Summary

Of course, the more things that you can relegate to the template, the less work you will have to start off on a project. Templates can help you generate virtual environments, install packages, initiate git repositories, create links to your favorite databases, setting up licensing agreements, create unit-testing and autodoc frameworks, frameworks for version checking, binaries for uploading local files to AWS instances, and much more.

The needs for every project is different. A Kaggle competition might not need unit-testing but will probably need your favorite recipes for exploratory analysis and typical feature generations baked-in from the beginning. Certain projects might need data-persistence and data-versioning, while others might need accesses to external databases and standard ETL. However, if you decide on proper structure at the onset, and believe that that might be a good general structure to begin with, you will not have to worry about the boring parts of programming more than once.

Look up the available cookiecutters here. There are already a number of cookiecutters available. If one doesn’t suit you, make your own, or just modify one.

Further Reading

There are many Python-specific things that have been glossed over. Some of the following links might be useful for those unfamiliar with Python.